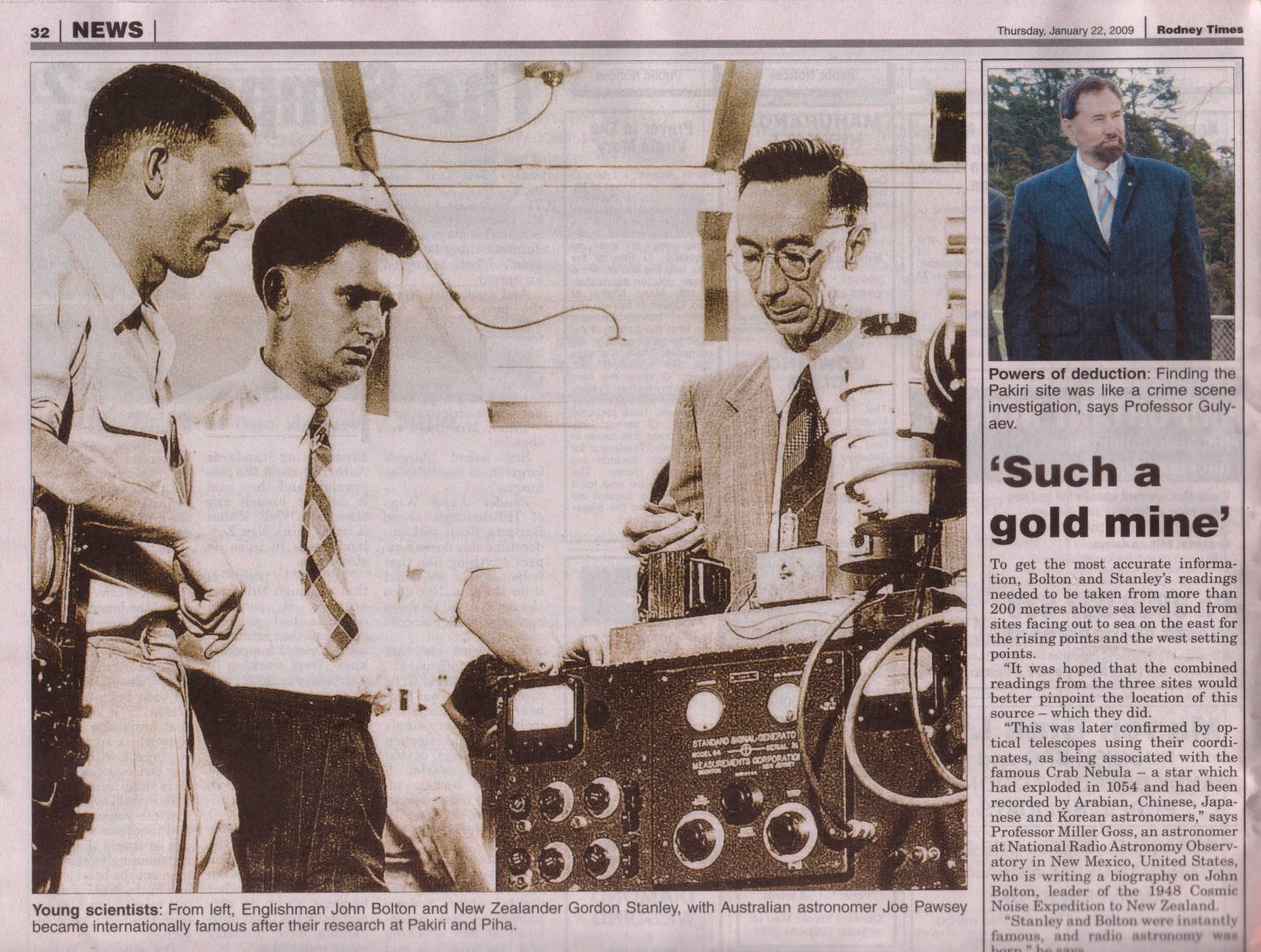

On Tuesday 17 November 2009 a small disparate group of people gathered on the regional parkland at the end of Log Race Race, Piha, on a strange expedition. The leader of the group was a tall lanky American, Dr Miller Goss, a radio astronomer from the National Astronomy Observatory in New Mexico. Goss was on the trail of two pioneering radio astronomers, John Bolton and Gordon Stanley, of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Sydney. In 1948, at this very place, they had detected and accurately positioned the sources of radio waves from the Crab Nebula, the most famous and most studied object in all of astronomy. Part of the Milky Way Galaxy, the Crab Nebula is described as the tattered remnants of a supernova which exploded in 1054.

With the aid of ARC park rangers and historians and some long-term residents of the area, Goss was hoping to find the exact spot where the two astronomers had set up their portable antennae.

Frustrated at the lack of high ground in Australia, Bolton and Kiwi-born Stanley had brought their Cosmic Noise Expedition over the Tasman to New Zealand. The pair went first to Pakiri where for two cold winter months they sat nightly observing the heavens, their lonely task leavened by the kindness of the Greenwood family on whose farm they had set themselves up. Mrs Greenwood brought tea and sandwiches in the early hours of the morning, and to Goss’s delight, the family, still living on the family farm, had kept wonderful records of the visit.

But success eluded Bolton and Stanley, so on 26 July1948 they went to the WW2 radar station at Piha, where the cliffs are the highest in New Zealand and face west.

They were taken in by the caretaker of the mothballed radar station, Don Taylor, and his wife, Lorraine. The radar station had reliable power because there was a generator and the weather was by then more settled. They set up their portable Yagi antennae on the cliff-top. Radio signals can be detected from stars, the moon or the sun. Bolton and Stanley were looking to perfect the positions of radio sources outside of the sun, and they succeeded within a short time of their arrival at Piha. They were able to measure the position of four radio stars by plotting their path above the horizon between rising and setting. This enabled them to work out their celestial coordinates.

When Goss talks about the Bolton and Stanley expedition he is full of superlatives. This was a monumental discovery – the first discovery of a celestial object that was not the sun or the moon. The supernova had first been observed by Chinese astronomers in 1054. Bolton and Stanley’s discovery revolutionised twentieth century astronomy.

Much of the old radar station site is now a carpark, but at the western end there is a marine beacon and the concrete ruins of various structures. With the aid of old photos and plans, Goss and his assistants were able to locate the foundations of the station radar and sections of the high barbed wire perimeter fence within the bush. A photo provided by Mrs Taylor enabled Goss to exactly pinpoint where Bolton and Stanley’s travelling antenna had stood.

Goss and other astronomers are very keen to see the location of this internationally important experiment marked in some way, a potential pilgrimage point for radio astronomers. Soon it will see visitors of another kind as the Hillary Trail goes past it. Goss plans to devote a chapter of a book he is writing to Bolton and Stanley’s New Zealand discoveries.

Wayne Orchiston wrote this academic paper about the project “John Bolton, Discrete Sources, and the New Zealand Field-trip of 1948”, Aust J Phys, 1994, 47, 541-7 orchiston.nz.expedition

To find out more about the Pakiri end of the story read this story from the Rodney Times